By Tom Mueller

It’s a busy workday – a normal workday – with lots to do and deadlines approaching, and in the midst of this your computer stops working. You want to save the document you’re working on, but it’s no use. You’ve lost it.

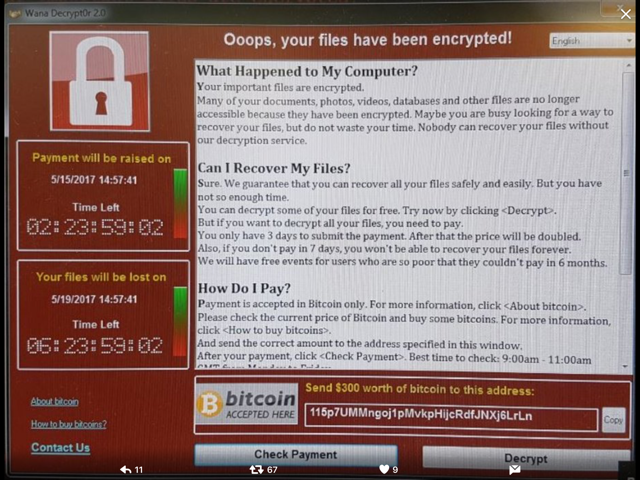

Then a new page appears on your display. It’s a politely-worded page demanding a ransom payment in order to unlock the files on your computer. Everyone on your team and on your floor are now staring at this same screen. And the malware that caused it is still spreading – maybe across your entire company.

Within a few hours, you’ve lost all or nearly all of your company laptops to this ransomware. What now, my friend? You need to provide guidance and leadership to your global organization. How do you keep communications flowing?

If your organization has migrated systems to the Cloud, you can simply switch to the cloud-based software tools. Microsoft’s Office.com is a cloud-based version of the tools you use on your laptop. So migrate your communications operations to that platform.

Your staff know how to access and use the tools there, right? I work on the cloud-based tools regularly and I can tell you these tools are not identical to those on your laptop. The names are the same – Outlook, Onedrive, PowerPoint – but the functionality is not always the same. That’s why your staff need to use these alternate tools regularly and become familiar with the differences.

The black swan event

In the black swan version of this ransomware event, you may lose your single-sign-on capability, which could eliminate access to your network, your email, your VOIP phone capability, and your ability to communicate across your organization. The backup Cloud-based tools I mentioned earlier generally work using the single sign on technology. They could be out of reach now.

You may even have lost operational control of your operating facilities if they use computer process controls.

The black swan has landed. What now?

Step 1: Re-establish communications to key personnel and offices. Seems simple enough, but if you’ve lost email and your internal communication channels, and your phone system is disrupted, you need alternatives.

Keep it simple – go where employees and managers already are: messaging apps. While these apps (WhatsApp, FB Messenger, etc.) may not meet company guidelines for business as usual communication activities, in a major crisis they may be just the thing you need to re-establish connectivity.

Step 2: Gather up the team. Use these messaging apps or other tools to host a conference call to assess your situation. The field of crisis apps is expanding rapidly today, with several good options that would allow you to quickly host a conference call directly from the app. Your crisis plan can also be stored in the app, along with checklists, contact lists, and more.

Step 3: Implement your cyber crisis response plan. This assumes you have a cyber response plan. If you don’t, then it’s time to show your improvisation skills. But better to have a plan in place, no?

How will you write employee update notes, press releases, investor updates and the many other communications that you’ll need to manage? Will your IT department have lots of extra laptops laying around you can borrow? Will your team be at the top of the priority list for those few available laptops? You may find yourself headed to Best Buy with a company credit card.

Back from Best Buy, you now have an arm load of laptops that won’t connect to your downed network. How will you print your documents for approvals? How will you email them for approval – and to what email addresses? Do you have backup email addresses off-network that you could rely on in this scenario? If your staff are working remotely from home, what devices can they use to access your response tools? Do they have those devices in hand?

The answers to these questions aren’t necessarily difficult, but they do require some planning and some dogged attention by someone on your team. This might be a special assignment – perhaps a developmental assignment – for someone to build the plan and backup systems, and develop some training materials. But it won’t happen unless it is set as a clear priority and supported by senior leadership.